As we all know by now, when it comes to academia, I’m pretty chill. I’m both easy and breezy, and I am hardly vengeful at all. So it takes a lot to make me sit down and type furiously at this keyboard brimming as I am with righteous indignation. Although the fact that an earlier post was exactly that does kinda undermine my argument… Anyway, a couple of times recently, I’ve been presented with the same frustrating argument that I’ve heard countless times before. And while I usually ignore it, these times it was said online in front of a considerable number of people. So I feel that I need to unpack it a bit for fairness and I thought this would be the best place to address the claims. It’s an argument I’ve heard since I started out in forensic anthropology. Now, although I am basically the Paul Rudd of the forensic world, and have seemingly not aged since I was 26, I’ve actually been doing this for 20 years now. That’s two decades of hearing this bollocks. The argument is about as logical as the Fast and Furious franchise, and like that, gets increasingly ludicrous with each iteration (little Easter egg there for FF fans…).

The question in, well, question, is whether we should be teaching forensic anthropology when there are no jobs in forensic anthropology. I’ve had this thrown at me for years and I always wonder why people care so much? Especially since those who tend to ask this question are not forensic anthropologists. It seems like there’s some form of snobbinshness about the subject. I mean, how many of us are actually telling students that a degree in forensic anthropology will guarantee them a job in forensic anthropology. And why is forensic anthropology being singled out? Why do we think course leaders of forensic anth degrees are saying this, but course leaders in sociology or computer science aren’t? A quick check of What Uni? records two entries for undergrad forensic anthropology (but there are at least 5 in the UK at the moment), whereas it had 111 institutions offering 1453 entries for UG history. So are we somehow less honest than these other disciplines?

Crucially, it’s also an argument that removes student agency from the equation. It says that students can’t study what interests them, but rather what others say they can study. Not every student who starts a degree wants to spend the rest of their lives doing that. A recent British Academy report notes that there were 10,000 students studying theology and religious studies in the UK in 2019. I’m pretty sure they’re not all becoming priests. From my own experience I know that when I started my undergraduate degree in Archaeological Science and Geography, I didn’t want to be an archaeologist or a geographer. I wanted to be a teacher. Then just before I graduated, my grandparents died and left me a couple of thousand pounds and I decided the most fitting thing to do with that money was use it to pay the tuition fees on a Masters degree, which I supplemented by working the worst job I have ever had (a story for another time). I chose an MSc in Forensic Anthropology because I was super-interested in studying the skeleton. It was only later, towards the end of my MSc, when I realised that this was what I actually wanted to do as a career.

Yes, some of these degrees are really popular and have large student numbers. But that’s said like it’s a bad thing. UCL does well with their forensic provision, but then they are UCL, are in London and have both star academic Prof Ruth Morgan and international cognitive bias guru Dr Sherry Nakhaeizadeh. Cranfield has the enviable double-act of Dr Nick Marquez-Grant and Dr Dave Errickson and you can literally shoot stuff there. UCLan has a fully-functioning taphonomy centre. Excuse me while I sit down and fan myself to recover from the shock of students wanting to study somewhere exciting. And you know what, all of these require significant institutional investment and support.

Besides why shouldn’t universities make money (I’m hoping our COO reads this so he knows that I’m totally on message…). Ignoring the fact that we’re technically charities and so can’t make a sizable profit, the UK higher education sector has been marketised. In the UK, money follows the student now, so without our students we won’t have enough money to sustain our institutions. This has been brought into stark light during the pandemic when students have been sent back to campus. Even research intensive unis recognise that research is a loss-leader and student income is needed to cross-supplement other areas of activity. We can yearn for it to be this purer, higher form of existence, something nobler and unblemished, like Tom Hanks, but it’s not been that way for years. A strong financial position ensures the longevity of our universities, plus our work and the credibility of our students’ qualifications.

The argument then assumes that because these are quick money-makers, they are also of a poor quality. We are therefore exploiting our students twice – once in terms of employability and once in terms of academic rigour. I say again. Fuck the fuck off. UK forensic anthropology degrees go through the same quality approval and external examiner process as every other degree. I know this because I have been involved in all aspects of this process at a number of different universities. Hell, I’m even paid by other universities to consult on their plans for teaching this subject. The external examiner process works too, because we have seen at least one degree get closed down because of it. But lets also note that forensic anthropology degrees can also be accredited by the professional body, the Chartered Society of Forensic Sciences. There’s been an increasing number of publications on teaching within forensic anthropology, and I actually published on this very subject back in 2003. I would argue that this sharing of good practice and evaluation of interventions is a sign of disciplinary maturity. Check out the special issue of Forensic Anthropology as an example.

Look, I know that as basically the Henry Cavill of the forensic world, it’s easy to be distracted by all of this and not really hear what I’m saying, but the truth is that the oft-quoted forensic degree bubble has long since burst and we now have a fairly stable number of courses. There was a crazy explosion of courses about 15-20 years ago, but these have rescinded over time as different topics became popular with students. As I said above, we’re working in a fluid marketplace, and so we need to offer provision that is attractive. Besides, for all of the criticism of those forensic degrees, they absolutely saved a number of chemistry and biology departments. People literally kept their jobs because of it. And now those departments have been developing new courses in chemistry and the biosciences again. Things they wouldn’t have been able to do if they had closed. Trends in HE are circular. Oh, and you know what, forensic science is really bloody interesting. We know from our own institution that it has resulted in students (often first gen) coming to university to study science who wouldn’t have done so previously. Essentially the degrees give you a really broad scientific background, covering as they do biology, chemistry, maths, psychology, philosophy, law, archaeology, geology and so on and so on. And those students have gone on to work as crime scene scientists and forensic lab techs. But also teachers, and lab analysts, police officers and QA specialists, health and safety experts and countless other careers where a good understanding of science combined with critical analysis and data management skills are needed.

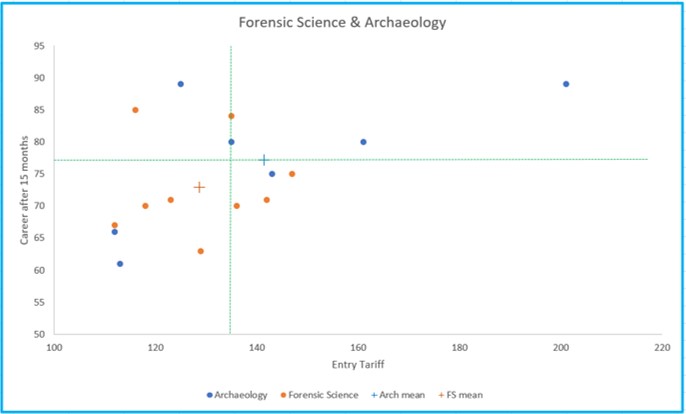

The graph below is taken from data presented in The Guardian 2021 University League Table. If you search by subject, and wade through the data (which I did because it’s the sort of thing I do to make a point), then you can start to see if there are any real differences between the employability of archaeology degrees (which I’ve chosen because often those who criticise forensic anthropology come from this discipline) compared to those in forensic science when mapped against entry tariffs (which is a proxy for exclusivity). Each data point below is a UK university, and the green lines represent the sectoral means for all institutions and all subjects. So what do we see? Well, if you ignore the blue outliers (Oxford and Durham), its a bit of a mix. Universities offering predominantly archaeology show slightly higher long-term employability, but not in all cases. But then they also have higher entry requirements, which tends to mean a) ‘better’ students and b) ‘better’ reputations – both of which improve employment chances. Albeit arguably because of greater networking opportunities and greater social capital of the students. Further, these league tables tend to record graduate jobs, which often excludes the likes of policing. What we do see is that, on the whole, universities offering forensic science engage in stronger widening participation initiatives (so lower tariffs). Anyway, this is all a really petty way of me pointing out that doing forensic science does not mean that you have a lower chance of long-term employability. There are jobs out there.

At Teesside, we don’t actually run forensic anthropology degrees because my aim has always been to create a centre of excellence for research. Which I think we’ve done. Of the 11 PhD completions I’ve had so far: four are working in academia, four are working in human rights contexts, two are working in the heritage sector and 1 is a forensic physician. I am hugely proud of all of them and they are all making a fantastic contribution to the subject. And this is my point here (other that showing off about how amazing my PhDers are). There is actually a lot of work for those with qualifications in forensic anthropology. And the work is important. This idea that it’s glorified osteology for the police is, again, snobbishness. Look at the work following periods of mass violence; look at who is leading the investigation of our global refugee crisis; look at who are defining biological patterns of abuse. Forensic anthropologists.

Could the media be more responsible with how they portray forensic anthropology? Of course. But, to be fair, that’s not their job. Their job is to sell stories or get viewers. And how is it my job to monitor what the press say? I’m not Ofcom. Forensic anthropology has a human connection both through those who do the work, and those who we study. The public are fascinated by the subject. Our online Future Learn course (Forensic Archaeology and Anthropology) was ostensibly written for those working in the field so we were a little taken aback by the sheer number of people who have studied it – we’re at over 20,000 so far. These are interested members of the public from all over the world, fascinated by the subject and excited to learn more from the experts. There’s a recognition that the subject is not really like it is portrayed on TV, and they wanted to know the truth. We even know that the CSI Effect is being questioned now as ‘a thing’. But is archaeology portrayed any differently? I’ve done excavations. It’s nothing like Time Team. Bone Detectives is excellent, but as a rule, in real life we like to turn the lights on when we work. So let’s not pretend that forensic anthropology is portrayed any less honestly than any other subject involving human remains.

So what to do? Well, nothing. In the same way that we do nothing about every other subject. Those who teach forensic anthropology in universities have a responsibility to be honest with our students and to ensure that our teaching material is current. But that’s true for every subject. I can only assume that the special attention forensic anthropology gets is because it’s a comparatively young discipline compared to many others. But really, this question is pretty out of date now. We can stop asking ‘should we be teaching forensic anthropology?’ and start asking ‘how should we be teaching forensic anthropology?’. As someone who has made a successful career as an academic in forensic anthropology, I am not about the pull the ladder up on those who, like me, were fascinated by the subject and just wanted to learn.