Here’s the secret if you want to get me to do something for you. Flattery. And asking for the favour months and months in advance. So far in advance, as a matter of fact, that you can see in my eyes that I’m going “Huh, that’s ages away, I have plenty of time to sort that out. No need to worry about that now”. Of course, I’ve been around long enough now that I can absolutely spot when flattery is being thrown at me. But it’ll mostly still work. Just last week I was caught by someone as I was exiting a lift who basically went “Tim! I was just looking for you! Can you give a presentation for us? It’s in September and you’d be great”. Anyway, I’m giving a presentation in September if you want to come along.

This is largely how I ended up giving a webinar presentation as part of the Chartered Society of Forensic Sciences Learning & Teaching webinar series. In my time as President, we’ve worked hard to create a stronger community of forensic science educators. This has included creating new and helpful supports and opportunities to share experiences. Most of our members are connected with universities in some capacity, and given the current HE context in the UK, we want to ensure that the forensic sciences remain a higher education success story through innovation, shared good practice, and collegiality.

I was asked by Dr Helen Tidy (through flattery and with the benefit of many months advance notice) to talk about how to publish learning & teaching work. It’s something that I have some experience of, but I’ve also been an Editor-in-Chief of two journals, and both times have delivered an increased L&T output for those publications.

It’s hard to get your first publications under your belt. There are a whole bunch of unwritten rules that no-one tells you about. I always recommend writing your first few papers with more experienced people, or at least with a mentor, while you figure it all out. This includes the whole submission process which is so much more stressful and time-consuming than you think it’ll be. I still remember the frustration of going through it myself and learning these lessons the hard way. My very first paper was desk rejected, and I still remember how much that stung as a fresh-faced twenty-four year old. Hell, it can still be a frustrating process for me now. My last publication went through four peer reviewers, and that’s not even the most one of my papers has ever had. The one I’m sitting on now has had some super reviewer comments and it’s still getting rejected! There are journals I refuse to submit papers to because they treated me so badly when I was a less experienced academic. One time I was asked to peer review my own paper. Another time my paper was a week away from publication when the journal realised that they had made a mistake and took the paper back to the start.

When Wilson Phillips iconically sang:

You could sustain (you could sustain); Or are you comfortable with the pain?

You’ve got no one to blame for your unhappiness (no, baby); You got yourself into your own mess (oooh…)

Lettin’ your worries pass you by (lettin’ your worries pass you by); Baby, don’t you think it’s worth your time

To change your mind? (no, no); Some day somebody’s gonna make you want to turn around and say goodbye

Until then, baby, are you going to let ’em hold you down and make you cry?; Don’t you know?

Don’t you know, things can change; Things’ll go your way

If you hold… on for one more day; Can you hold… on for one more day?

We all agree that they were singing about the academic publication process, right?

Okay, this isn’t helping anyone and all it’s doing is highlighting to everyone that I am not very good at letting things go…

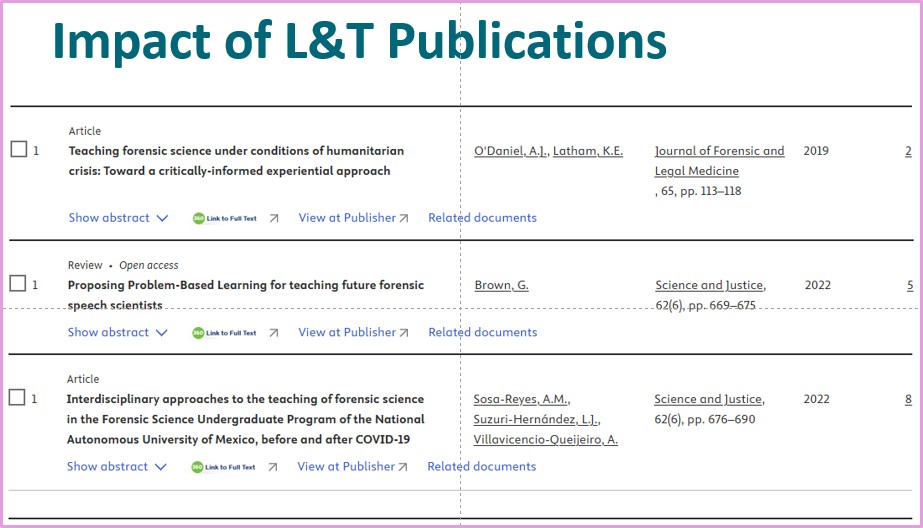

Back to the webinar. First of all, I wanted to set the scene a little for the audience. So I looked at the top 50 most cited publications in Science & Justice, Forensic Science International: Synergy, Journal of Forensic & Legal Medicine and the Journal of Forensic Sciences. I chose these four because I knew for sure that they had published L&T papers. Of the 200 papers in this collection, just one concerns learning and teaching. That one is Virtual reality for teaching and learning in crime scene investigation (2020) by Richard Mayne and Helen Green which has come in at #38 of the most cited papers in Science & Justice. That’s not ideal, given the importance of university education in the development of forensic science and forensic scientists. Clearly research in L&T is not as popular as other research topics. That makes sense. It’s partly about ease and opportunity – it’s much easier to get an MSc student to do a lab-based project to validate a method of presumptive testing than to validate a method of engaging students in a weekly seminar. So the volume of opportunities lies with non-pedagogical research. They also lend themselves to more straightforward writing of articles of the Intro-Method-Results-Discussion-Conclusion variety. Nothing wrong with that at all. The other issue is that pedagogical research is not taken as seriously in other aspects of academic work, like promotion. It doesn’t draw in the funding or the esteem indicators and over the years I’ve certainly seen pedagogical papers viewed as less significant than ‘pure’ science papers.

And all of this comes at a time when academics are questioning the quality of scientific papers in the age of easily accessible AI as well as the impossibility of keeping on top of the increasing number of scientific publications in our areas of interest.

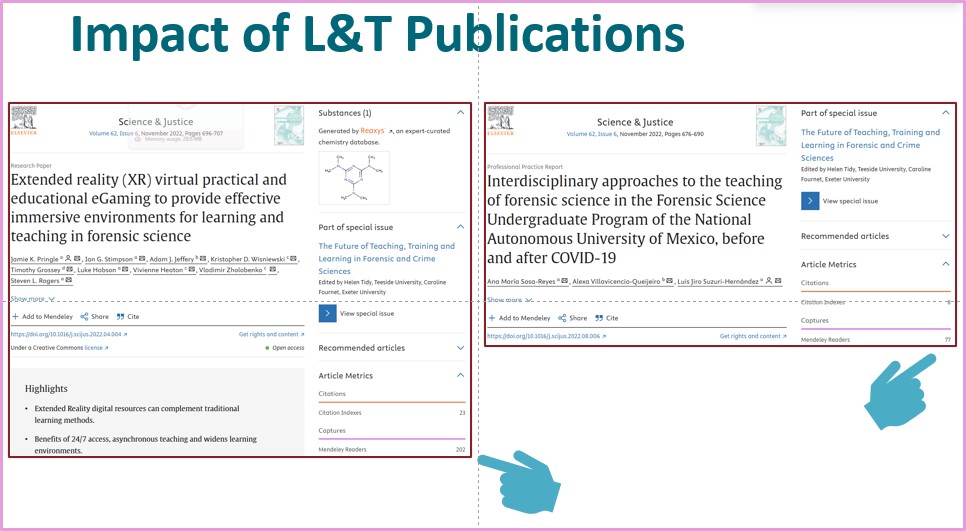

But if we look a little closer at the articles metrics of our forensic pedagogical publications, what we see is that the papers may not be getting many citations, but they are getting read. Which implies that these outputs are making a positive contribution to the field, and may be influencing practice just as we’d hope. It’s just a little bit unseen, which is a little bit frustrating.

And so I concluded the webinar with what I felt were some practical steps to help my earlier career colleagues.

1. Demonstrate the impact of your interventions:

- What did the students think?

- How did student outcomes change?

Basically, you need to be able to show that whatever intervention of activity you have told us about in your paper has had some form of impact beyond just being an interesting thing that you’ve done. And if you can, make the university care about your work by linking the impact to something that the university cares about – retention, attainment, student satisfaction, finances.

Here are a couple of papers which built evaluation into their methods and could therefore demonstrate impact:

- Choose your own murder: Non-linear narratives enhance student understanding in forensic science education

- Engaging students through storytelling: A fictitious crime project

2. Choose the right journal:

- Have you ever read an L&T journal?

- What comes into your email inbox?

I don’t publish in learning & teaching journals because I think the only people who read learning & teaching journals are those academics who are interested in learning & teaching and I don’t believe most academics are so interested in learning & teaching that they’ll go off and read a learning & teaching journal. Now, that may feel controversial, but think about what journals you have come automatically into your inbox. Are they disciplinary or pedagogical? What journal alerts do you have set up? Are they disciplinary or pedagogical? I have no idea how you’re responding as this is a piece of inert writing, but I’m going to assume that you’re frowning and nodding in agreement. I’ve always felt that if I want forensic scientists to read about my pedagogical work then I should publish in a forensic science journal.

Here are a couple of examples of academics tackling challenging pedagogical issues but publishing them in disciplinary journals (rather than the more common pedagogical journals) to increase the likelihood that they will be read and considered in these disciplines:

- Approaches to decolonising forensic curricula

- Decolonising forensic odontology in Sub-Saharan Africa

3. Think about what you are trying to tell us?

- New approaches? New methods? Different student cohorts?

- Is this novel or just the usual?

Sometimes I’ve been a peer reviewer on a paper which has been really well written and is an interesting case study, but it doesn’t really say anything that we don’t already know. Just be confident that what you’re saying is actually novel and new. The best way to check is to get some critical friend feedback.

Here are a couple of papers that present something new via their case-study format:

- Interdisciplinary approaches to the teaching of forensic science in the Forensic Science Undergraduate Program of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, before and after COVID-19

- Enhancing the student learning experience through memes

And then another, which is a good paper but doesn’t present anything spectacularly new:

And that was it, really. Hopefully the webinar (and this summary) gave a little context for those interested in publishing in this area and supports the experimental and risk-taking approach that forensic science educators often take, but don’t necessarily shout about. But I know you’ll all say how helpful this has been, because you now know how effective flattery is…